The intricate relationship between our gut and cancer is one of the most groundbreaking areas of research in modern medicine. It’s a field that continually challenges our understanding of the human body, moving far beyond the traditional view of the gut as a mere digestive organ. Instead, we now see the gut as a dynamic and complex ecosystem—a bustling metropolis of microorganisms that significantly influences our immune system, metabolism, and susceptibility to diseases, including cancer. This article delves deep into this fascinating connection, providing a comprehensive, holistic, and evidence-based overview of why gut health is vital for cancer prevention, and how specific dietary and lifestyle strategies can play a pivotal role.

A Historical Perspective: Timeline of Key Discoveries

To truly appreciate the current understanding of the gut-cancer connection, it’s crucial to acknowledge the historical timeline of key discoveries that have shaped our knowledge.

Pioneers in Microbiome and Cancer Research:

- 1860s - Louis Pasteur: (Germ Theory) Pasteur's work established that microorganisms cause fermentation and disease, laying the foundation for understanding the role of microbes in health.

- 1880s - Robert Koch: (Koch's Postulates) Koch's postulates helped solidify the causal link between specific microorganisms and specific diseases. This formed a basic understanding of how infections can affect human health, which later could be applied to other fields of research.

- 1900s - Élie Metchnikoff: (Probiotics and Immunity) Metchnikoff proposed that the bacteria in the gut could influence health and aging and even proposed that consuming lactic acid bacteria could prolong life, a concept that laid the groundwork for future probiotics research.

- 1908 - Paul Ehrlich: (Immune System) Ehrlich's work on immunity introduced the concept of a specialized immune system that can target and destroy invaders. This laid the foundation for later research into how the immune system interacts with the microbiome.

- 1950s - Rene Dubos: (Ecological Perspective) Dubos emphasized the dynamic interaction between microbes and their environment, highlighting the complex ecology of the gut. Dubos work promoted the idea that microorganisms are not just pathogens but could have a beneficial role.

- 1970s-1980s - Early Human Microbiome Research: Researchers begin using culture-based methods to study gut bacteria, although this approach could not capture the true diversity of the microbiome.

- Early 2000s - Human Microbiome Project (HMP): This large-scale project utilized metagenomic sequencing to provide a comprehensive picture of the human microbiome, including the gut, revolutionizing our understanding of the microbial communities in our bodies. The HMP helped to show the diversity of the human microbiome, its metabolic potential, and its role in health and disease.

- 2000s onwards - Growing Understanding of the Gut-Cancer Axis: Increasingly sophisticated research demonstrates the profound impact of the gut microbiome on cancer development, progression, and treatment response.

- Current Day - Ongoing Research and Therapeutic Applications: Today, scientists are focused on personalized microbiome interventions, like fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) and dietary approaches, as well as developing therapies that can target specific microbial populations in order to fight cancer.

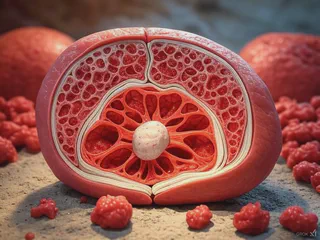

The Gut: A Complex Ecosystem Beyond Digestion

The gut, often referred to as the gastrointestinal tract, is far more than just a digestive organ. It’s a vast and dynamic ecosystem hosting trillions of microorganisms, collectively known as the gut microbiome. This complex community, comprising bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microbes, plays a vital role in numerous physiological processes that go far beyond breaking down food.

The gut microbiome is instrumental in:

- Nutrient Acquisition and Metabolism: The gut microbiome aids in the digestion of complex carbohydrates, which would be indigestible for humans otherwise. They also produce essential vitamins, like vitamin K and certain B vitamins, which our bodies cannot synthesize on their own. Further, they ferment indigestible fibers, producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) which have numerous health benefits.

- Immune System Regulation: A significant portion of our immune system resides in the gut. The gut microbiome helps train and regulate immune cells, influencing their response to pathogens, allergens, and cancer cells. This training is essential to ensure the immune system can distinguish between harmful invaders and the body’s own tissues. You can learn more about the immune system in our article on understanding the immune system.

- Maintaining Gut Barrier Integrity: The gut lining acts as a selective barrier, allowing the passage of nutrients while preventing harmful substances from entering the bloodstream. The gut microbiome plays a critical role in maintaining the integrity of this barrier, preventing “leaky gut” and the systemic inflammation associated with it.

- Neurological Signaling (Gut-Brain Axis): The gut communicates with the brain through a complex network of nerves and signaling molecules, known as the gut-brain axis. This bidirectional communication is crucial for regulating mood, stress response, and even cognitive functions. Disruptions in gut health can impact neurological function, and vice versa. For more information, see our article on the gut-brain axis.

- Production of Bioactive Compounds: Gut microbes produce a vast array of bioactive compounds that influence our health, including SCFAs, neurotransmitters, and various signaling molecules that can impact metabolism, inflammation, and immunity.

The Intricate Link Between Gut Health and Cancer

The relationship between the gut and cancer is a two-way street: a compromised gut can contribute to cancer development and progression, and cancer and its treatments can further impact gut health. This section explores why gut health is so critical for cancer prevention.

1. The Balancing Act of the Microbiome: Eubiosis vs. Dysbiosis

A balanced gut microbiome, or eubiosis, is characterized by a diverse and abundant community of beneficial microbes. This diverse population of beneficial microbes is critical to ensure a stable and resilient gut ecosystem that is able to perform essential functions that promotes health and reduces risk of diseases. Conversely, dysbiosis is an imbalance in the microbiome with a reduced diversity of beneficial microbes, which can promote inflammation, impair immune function, and contribute to cancer risk. We explored this topic in more detail in our article on gut dysbiosis.

- Beneficial Bacteria (Commensals): These include species like Bifidobacteria, Lactobacillus, and Akkermansia. These microbes produce compounds that can inhibit tumor growth, modulate the immune system, maintain gut barrier integrity, and produce beneficial SCFAs like butyrate. They also play a role in the synthesis of essential vitamins and amino acids, and in the detoxification of harmful compounds.

- Harmful Bacteria (Pathobionts): Certain bacteria, such as some species of Fusobacterium, Bacteroides, and Escherichia coli can promote inflammation, produce toxic metabolites, and disrupt the gut barrier. An overgrowth of these harmful bacteria can contribute to cancer development and progression by creating a microenvironment that is beneficial to tumor growth.

- Influencing Factors: Diet, lifestyle, stress, medications (especially antibiotics), and even genetic predisposition can impact the balance of the gut microbiome.

2. The Role of Inflammation in Cancer Development

Chronic inflammation is a key factor in the development and progression of many types of cancer. The gut is a major site of inflammation, and gut dysbiosis can contribute to chronic, low-grade inflammation throughout the body. You can learn more about how to manage this in our article about anti-inflammatory diets.

- Inflammatory Pathways: Gut dysbiosis can activate pro-inflammatory pathways, leading to an increase in inflammatory cytokines and other signaling molecules that promote systemic inflammation.

- Leaky Gut: A compromised gut barrier, or leaky gut, allows harmful substances to enter the bloodstream, further fueling inflammation. This systemic inflammation creates a microenvironment that supports tumor growth, angiogenesis (formation of new blood vessels needed by tumors), and metastasis.

- Inflammation and Tumor Progression: Chronic inflammation can lead to DNA damage, promote the survival and proliferation of cancer cells, and hinder the immune system's ability to fight against tumors.

3. The Immune System's Guardian Role

The gut microbiome plays a critical role in shaping and regulating the immune system, impacting its ability to recognize and eliminate cancer cells. We discussed the importance of the immune system in our article on understanding the immune system.

- Immune Cell Education: The gut microbiome helps “educate” immune cells, allowing them to distinguish between harmful invaders and the body’s own tissues, fostering a balanced immune response.

- Immune Cell Activation: The gut microbiome can stimulate the activity of immune cells like T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, which are crucial for directly attacking and destroying cancer cells.

- Immunomodulation: A healthy gut helps ensure an efficient immune response, preventing both excessive inflammation and an underactive response that can allow cancer cells to evade detection.

- Dysbiosis and Immunosuppression: Dysbiosis and chronic inflammation in the gut can impair the immune system, decreasing the body's ability to fight against cancer. In some cases, cancer cells use this immunosuppression to their advantage by suppressing the immune response.

4. Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) and Gut Health

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), particularly butyrate, acetate, and propionate, are produced when beneficial gut microbes ferment dietary fiber. These SCFAs have profound effects on gut health and play a significant role in cancer prevention. We have explored the benefits of dietary fiber for gut health, and how dietary fiber can influence the gut microbiome in general.

- Anti-Inflammatory Effects: SCFAs, especially butyrate, have strong anti-inflammatory properties in the gut and throughout the body, reducing chronic inflammation that can promote cancer development.

- Colorectal Cancer Protection: Butyrate has been shown to promote the health of colon cells and induce apoptosis (programmed cell death) in colorectal cancer cells. It also protects the colonic lining and reduces inflammation associated with colorectal cancer.

- Gut Barrier Integrity: SCFAs help strengthen the gut lining, reducing the risk of leaky gut and the subsequent inflammation that could contribute to cancer.

- Metabolic Benefits: SCFAs are also involved in glucose homeostasis, insulin sensitivity, and weight management, which are all important for reducing the risk of metabolic disorders and their associated cancers.

5. Modulating Cancer Progression and Treatment Response

The gut microbiome can influence how cancer develops and responds to treatments:

- Tumor Microenvironment: Gut microbes can produce compounds that directly affect tumor cell growth, metabolism, and migration.

- Treatment Response: Emerging research indicates that the gut microbiome can significantly influence the effectiveness of cancer treatments like chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and radiation therapy. A balanced microbiome can improve response rates and reduce treatment side effects.

- Reducing Treatment Toxicity: Maintaining a healthy gut during cancer treatment can help alleviate severe side effects, such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and fatigue. It is becoming increasingly important to consider this in developing cancer therapies.

- Metastasis: Some studies suggest the gut microbiome can influence metastasis (spread of cancer to other organs).

The Anti-Cancer Diet: Evidence-Based Dietary Strategies

Diet is a powerful tool that can significantly impact the gut microbiome and, therefore, cancer risk. Here’s a detailed look at evidence-based dietary strategies:

1. The Power of Fiber: Feeding the Good Bacteria

Fiber is the preferred food source for beneficial gut bacteria and promotes the production of beneficial SCFAs.

- Diverse Plant Sources: Aim for a variety of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds. Each provides different types of fiber and essential nutrients.

- Resistant Starch: Focus on foods high in resistant starch like green bananas, legumes, and cooked and cooled potatoes. Resistant starch is a type of fiber that acts as a prebiotic, feeding beneficial bacteria.

- Recommended Intake: Aim for at least 25-30 grams of fiber per day. Gradually increase fiber intake to avoid digestive discomfort.

Scientific Evidence: Studies have shown that diets high in fiber are linked to reduced risk of colorectal cancer, breast cancer, and other cancers. Fiber consumption also promotes a balanced gut microbiome and reduces inflammation.

2. Antioxidants: Fighting Oxidative Stress

Antioxidants help protect cells from damage caused by free radicals and oxidative stress.

- Colorful Fruits and Vegetables: Berries (such as blueberries, raspberries, and strawberries), cruciferous vegetables (broccoli, cauliflower, kale, and Brussels sprouts), and dark leafy greens are packed with antioxidants.

- Spices and Herbs: Include spices like turmeric, ginger, and cinnamon, and herbs like basil, rosemary, and oregano in your diet. These are rich in bioactive compounds and have anti-inflammatory properties.

- Green Tea: Contains catechins, powerful antioxidants with potential gut health and immune-boosting benefits, as we discuss in our article about EGCG in green tea.

- Dark Chocolate: In moderation, dark chocolate with a high percentage of cacao can provide antioxidants. You may also be interested in our article about dark chocolate and gut health.

Scientific Evidence: Multiple studies have linked increased consumption of antioxidant-rich foods to reduced risk of various types of cancer. These compounds help reduce oxidative stress and DNA damage that can lead to tumor development.

3. Probiotics and Prebiotics: Supporting a Thriving Microbiome

Probiotics are live microorganisms, and prebiotics are types of fiber that act as food for beneficial gut bacteria.

- Probiotic-Rich Foods: Include foods like yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, and kombucha in your diet. For more on probiotic-rich food, check out our article on fermented foods.

- Prebiotic-Rich Foods: Include onions, garlic, leeks, asparagus, bananas, oats, and apples in your diet. For more information about prebiotic foods, see our article on prebiotics for gut health.

- Probiotic and Prebiotic Supplements: If dietary sources are insufficient, you can consider adding supplements after consultation with a healthcare professional. Learn more about the benefits of probiotics and the power of prebiotics.

Scientific Evidence: Probiotics have been shown to improve gut health, reduce inflammation, and enhance immune function. Prebiotics promote the growth of beneficial bacteria and the production of SCFAs, both of which are important for cancer prevention.

4. Healthy Fats: Focusing on Anti-Inflammatory Sources

Not all fats are created equal. Emphasize healthy fats with anti-inflammatory properties.

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Found in fatty fish (such as salmon, mackerel, and sardines), flaxseeds, chia seeds, and walnuts. Discover more about omega-3 fatty acids.

- Monounsaturated Fats: Found in avocados, olive oil, nuts, and seeds.

Scientific Evidence: Omega-3 fatty acids have been shown to reduce inflammation, support immune function, and potentially slow the growth of some types of cancer.

5. Limiting Inflammatory and Gut-Disrupting Foods: Avoiding the Negative Impact

Certain foods can negatively impact the gut microbiome, promote inflammation, and increase the risk of cancer. It is important to understand the impact of processed foods and make informed choices.

- Processed Foods: Limit processed foods, which are often high in unhealthy fats, refined sugars, and artificial additives.

- Red and Processed Meats: Limit consumption of red and processed meats, as these have been linked to increased cancer risk, particularly colorectal cancer.

- Refined Sugars: Limit added and refined sugars, which can promote inflammation and gut dysbiosis.

- Artificial Sweeteners: Reduce or avoid artificial sweeteners, as some can disrupt the gut microbiome, and be aware of the potential issues surrounding artificial sweeteners.

Scientific Evidence: Studies show that high consumption of processed foods, red and processed meats, and refined sugars is associated with inflammation, gut dysbiosis, and increased cancer risk.

A Sample Anti-Cancer Diet Plan: Putting it All Together

Here's an example of a daily anti-cancer diet that prioritizes gut health:

Breakfast:

- Oatmeal with berries, nuts, and chia seeds

- Plain Greek yogurt with a drizzle of honey and cinnamon

- Green tea

Lunch:

- Large salad with mixed greens, colorful vegetables, lentils, and avocado, with an olive oil and lemon dressing

- Whole-grain wrap with hummus, sprouts, and grilled chicken or tofu

Dinner:

- Baked salmon with roasted vegetables like broccoli, cauliflower, and sweet potatoes

- Quinoa or brown rice with garlic and herbs

- A side of kimchi or sauerkraut

Snacks:

- A handful of almonds or walnuts

- A piece of fruit (e.g., apple, banana)

- Plain yogurt with a sprinkle of flaxseeds

- A small portion of dark chocolate

Beverages:

- Water throughout the day. You can explore the value of hydration for gut health.

- Green tea or herbal teas

- Limit sugary drinks and alcohol

Holistic Approaches: Integrating Lifestyle Factors

Beyond diet, several lifestyle factors significantly influence gut health and cancer risk:

- Stress Management: Chronic stress can negatively impact the gut microbiome and promote inflammation. Engage in stress-reducing activities like meditation, yoga, and deep breathing. You can learn more in our article on stress management.

- Regular Exercise: Physical activity promotes gut health by increasing microbial diversity and reducing inflammation. Find the right balance of activity and rest, as we discuss in our article on exercise and gut health.

- Adequate Sleep: Poor sleep can disrupt the gut microbiome and increase inflammation. Aim for 7-9 hours of quality sleep per night. Prioritizing sleep hygiene is key, as explored in our article on sleep and immunity.

- Avoiding Smoking: Smoking can significantly damage the gut and increase the risk of many cancers.

- Responsible Antibiotic Use: Use antibiotics only when necessary and under medical supervision, as they can disrupt the gut microbiome.

The Future of Gut-Cancer Research

The field of gut-cancer research is rapidly evolving, and the future holds great promise for novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies:

- Personalized Microbiome Profiling: Developing advanced methods to analyze an individual’s gut microbiome to provide tailored recommendations for diet and lifestyle.

- Targeted Microbiome Modulation: Developing interventions like fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) and precision probiotics to restore microbial balance and enhance cancer treatment response. You can also explore the benefits of personalized medicine.

- Microbial Metabolites as Therapeutic Targets: Identifying and developing compounds that modulate microbial activity and enhance anti-cancer effects.

- Dietary Interventions in Cancer Treatment: Integrating dietary changes into cancer treatment plans to improve outcomes and minimize side effects.

- The Gut-Brain Axis and Cancer: Investigating how communication between the gut and brain contributes to cancer and treatment response.

Conclusion: A Holistic Path to Cancer Prevention

The gut-cancer connection is a complex and dynamic interaction that is central to our understanding of cancer development and prevention. By focusing on evidence-based strategies that include a diet rich in fiber, antioxidants, and probiotics; limiting processed foods and harmful fats; and incorporating lifestyle factors that support gut health, we can significantly reduce our risk of cancer and promote overall well-being. This journey toward better gut health is an integral part of a proactive, holistic approach to cancer prevention, and future research will undoubtedly provide further insights into the profound relationship between our gut and overall health. This is not merely a trend, but a fundamental shift in how we perceive our bodies, health, and the potential of nutrition and a healthy lifestyle to transform our well-being.

Disclaimer: The information in this article is for general knowledge and informational purposes only, and doesn't constitute medical advice. It’s essential to talk with a healthcare professional for any health concerns or before making decisions about your treatment plan, medications, or supplements. Self-treating can be risky, and it’s important to work with someone who can create a plan specifically for your needs.

Further Reading:

- Gut: The Inside Story of Our Body's Most Underrated Organ by Giulia Enders

- The Mind-Gut Connection: How the Hidden Conversation Within Our Bodies Impacts Our Mood, Our Choices, and Our Overall Health by Emeran Mayer

- Fiber Fueled: The Plant-Based Gut Health Program for Losing Weight, Restoring Your Health, and Optimizing Your Microbiome by Will Bulsiewicz

- Anti-Cancer: A New Way of Life by David Servan-Schreiber

- Radical Remission: Surviving Cancer Against All Odds by Kelly A. Turner, PhD

- Beating Cancer with Nutrition, Revised and Updated by Patrick Quillin, PhD, RD, CNS

- Foods to Fight Cancer: What to Eat to Reduce Your Risk by Richard Béliveau, PhD, and Denis Gingras, PhD

- The Cancer-Fighting Kitchen: Nourishing Big and Small Appetites During Cancer Treatment by Rebecca Katz with Mat Edelson

- Anti-Cancer Living: Transform Your Life and Health with the Mix of Six by Lorenzo Cohen, PhD, and Alison Jefferies, PhD

- How Not to Die: Discover the Foods Scientifically Proven to Prevent and Reverse Disease by Michael Greger, MD

References:

- (Sears, B. (2015). Anti-inflammatory Diets. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 34(sup1), 14-21. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07315724.2015.1080105)

- (Tilg, H., & Moschen, A. R. (2015). Food, immunity, and the microbiome. Gastroenterology, 148(6), 1107-1119. https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(15)00146-8/fulltext)

- (O'Keefe, S. J. (2016). Diet, microorganisms and their metabolites, and colon cancer. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 13(12), 691-706. https://www.nature.com/articles/nrgastro.2016.165)

- (Lim, S. S., Vos, T., Flaxman, A. D., Danaei, G., Shibuya, K., Adair-Rohani, H., ... & Ezzati, M. (2012). A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet, 380(9859), 2224-2260. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673612617668)

- (Calder, P. C. (2015). Marine omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes: effects, mechanisms and clinical relevance. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids, 1851(4), 469-484. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1388198114002273)

- (Minihane, A. M., Vinoy, S., Russell, W. R., Baka, A., Roche, H. M., Tuohy, K. M., ... & Calder, P. C. (2015). Low-grade inflammation, diet composition and health: current research evidence and its translation. British Journal of Nutrition, 114(7), 999-1012. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-of-nutrition/article/lowgrade-inflammation-diet-composition-and-health-current-research-evidence-and-its-translation/47D1D6A7A1B2F0D8CC28F2F3F91ACE7F)

- (Shivappa, N., Godos, J., Hébert, J. R., Wirth, M. D., Piuri, G., Speciani, A. F., & Grosso, G. (2017). Dietary inflammatory index and colorectal cancer risk—a meta-analysis. Nutrients, 9(9), 1043. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/9/9/1043)

- (Giugliano, D., Ceriello, A., & Esposito, K. (2006). The effects of diet on inflammation: emphasis on the metabolic syndrome. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 48(4), 677-685. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109706013350)

- (Cavicchia, P. P., Steck, S. E., Hurley, T. G., Hussey, J. R., Ma, Y., Ockene, I. S., & Hébert, J. R. (2009). A new dietary inflammatory index predicts interval changes in serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. The Journal of Nutrition, 139(12), 2365-2372. https://academic.oup.com/jn/article/139/12/2365/4670493)

- (Basu, A., Devaraj, S., & Jialal, I. (2006). Dietary factors that promote or retard inflammation. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 26(5), 995-1001. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/01.ATV.0000214295.86079.d1)